ⅠRelations between Japan and Mongolia in the 13th century

The first event recorded as the beginning of contacts between Japan and Mongolia was the Mongolian Invasion of Japan during the period under the Great Yuan (hereafter "Yuan"). After the conquest of Goryeo (the kingdom of Korea at that time), the Yuan frequently demanded an amicable relationship with Japan, but the Kamakura Shogunate refused to accept the demand. Therefore, allied forces from the Yuan and Goryeo attacked the northern part of Kyushu (the westernmost main island of Japan) twice, in 1274 and 1281.

The impact of the event on Japan was so important that there are various materials in Japan describing the situation at that time.

Diplomatic correspondence

Official letter from Mongol Empire to Japan

Official letter from Mongol Empire to Japan

"The Great Mongol Kingdom" (the Mongol Empire), founded in the early 13th century, expanded rapidly, and the Great Yuan Dynasty was established by Kublai Khan.

Prior to the Mongol invasion in October 1274, two diplomatic correspondences from the Mongolian Emperor Kublai were delivered in 1266 to Goryeo, which had become a vassal state.

One of them ordered the King of Goryeo to guide the envoys of the Mongol Empire to Japan, and the other asked the Emperor of Japan for an amicable relationship. The envoy from Goryeo arrived at the Dazaifu in 1268, carrying the official letter for Japan.

The letter was written by the Emperor of the Great Mongol Kingdom (Kublai Khan) to the Emperor of Japan, stating that since Japan, which had been in communication with China for a long time, had not sent any envoy to the Mongol Empire, the Mongol Empire had sent an envoy with a letter to Japan, and that they hoped to deepen their friendship and rapport in the future. However, the letter also suggested the use of force if Japan refused to accept the proposal of the Mongol Empire.

This material is a manuscript copy of a document from the temple Tōdai-ji in Nara Prefecture, Japan.

Journal of a noble to the Emperor describing the arrival of the Diplomatic correspondence from the Mongol Empire

Journal of a noble to the Emperor describing the arrival of the Diplomatic correspondence from the Mongol Empire

The Official Letter arrived at the Dazaifu, which was responsible for diplomacy and defense functions in Japan, was delivered to the Shogunate in Kamakura. Later, the Imperial Court in Kyoto officially received the Official Letter from the Shogunate on February 8, 1268. Rumors of the arrival of the Official Letter were already widely known to the warriors of the Shogunate and nobles of the Imperial Court.

The material is the journal of a noble in the middle of Kamakura period, KONOE Motohira, who served as chief advisor to the Emperor. It was held in the Momijiyama Library, the Tokugawa Shogun’s repository of books in Edo Castle, and the collection was later inherited by the Meiji government, and handed down to the NAJ as the Cabinet Library collection.

The journal describes the arrival of the Official Letter from Yuan and Goryeo, stating "This is such an unexpected and important event for the nation. Everyone had no other response but astonishment."

No reply was sent to this Official Letter. In response to the silence of the Shogunate, Kublai Khan sent another mission. Once again, the diplomats arrived in Tsushima Island with the Official Letters of the Yuan and Goryeo, but no reply was sent from Japan.

Mongol Invasions of Japan (Attacks by the Mongol Empire)

Illustrated account of the attacks by the Mongol Empire

Illustrated account of the attacks by the Mongol Empire

In response to Japan’s refusal of friendly intercourse, Kublai Khan ordered Goryeo to prepare 10,000 troops and 1,000 warships. Five missions from the Yuan Dynasty to Japan failed to bear fruit. While the Shogunate maintained silence, defense system were reinforced.

On October 5, 1274, a large number of warships appeared before Tsushima Island, and on October 14, they attacked Iki Island. This was the first Mongol Invasion.

TAKEZAKI Suenaga, a warrior of Higo Province (present-day Kumamoto Prefecture), rushed against the Yuan army with only five followers. Takezaki also fought in the battles against the Mongolian invasion in 1281, as recorded in scrolls, in both pictures and words, which became popular through copied manuscripts.

The scene shown here depicts Yuan soldiers shooting arrows at Takezaki on horseback during battle in 1274, while firearms named tetsuhau went off between them. Although the Yuan forces had the upper hand in the war, the Japanese side put up a good fight. Without a final victory, the ship withdrew.

Kublai Khan continued to send missions, but the Japanese continued to reject the request. Japan thought that another attack by the Yuan forces was inevitable and built a stone fortification 20 kilometers long to prepare for the battle.

In May 1281, the Goryeo forces reappeared in Tsushima Island, and in July, a large fleet of more than 140,000 soldiers and 4,000 warships from allied forces of Yuan, Goryeo etc, arrived at Hakata Bay. That was the second Mongol Invasion. Unlike the first attack, the Japanese, who had stone fortifications and regular foreign patrols, intercepted the Yuan forces. Furthermore, a storm destroyed much of the large fleet and the ships retreated.

Narratives describing the Mongol Invasions recorded by temples and shrines

Narratives describing the Mongol Invasions recorded by temples and shrines

The situation of the Mongol Invasions is also described in relation to the prayers in the tale created at shrines in the late Kamakura period, several decades after the Mongol Invasions.

This document is called the Hachimangu gudoki (or Hachimangudokun). It describes how, at the time of the Mongol invasion, prayers for Japan’s victory were held at many shrines and temples, stating the invasion was repelled by the power of shrines and temples. It suggests that the Mongol invasions had a great impact not only on the warriors, but also on Japanese religion.

This document is also one of the few documents written about the Tsushima and Iki Islands during the Mongol invasions. In the scene shown, a Japanese soldier only twelve or thirteen years old shot a small arrow to signal the start of the Japanese war, and the Yuan army laughed in unison. There are also accounts of Yuan infantrymen beating drums and gongs, releasing gunpowder bombs, shouting and retreating, and using short arrows coated with poison as weapons.

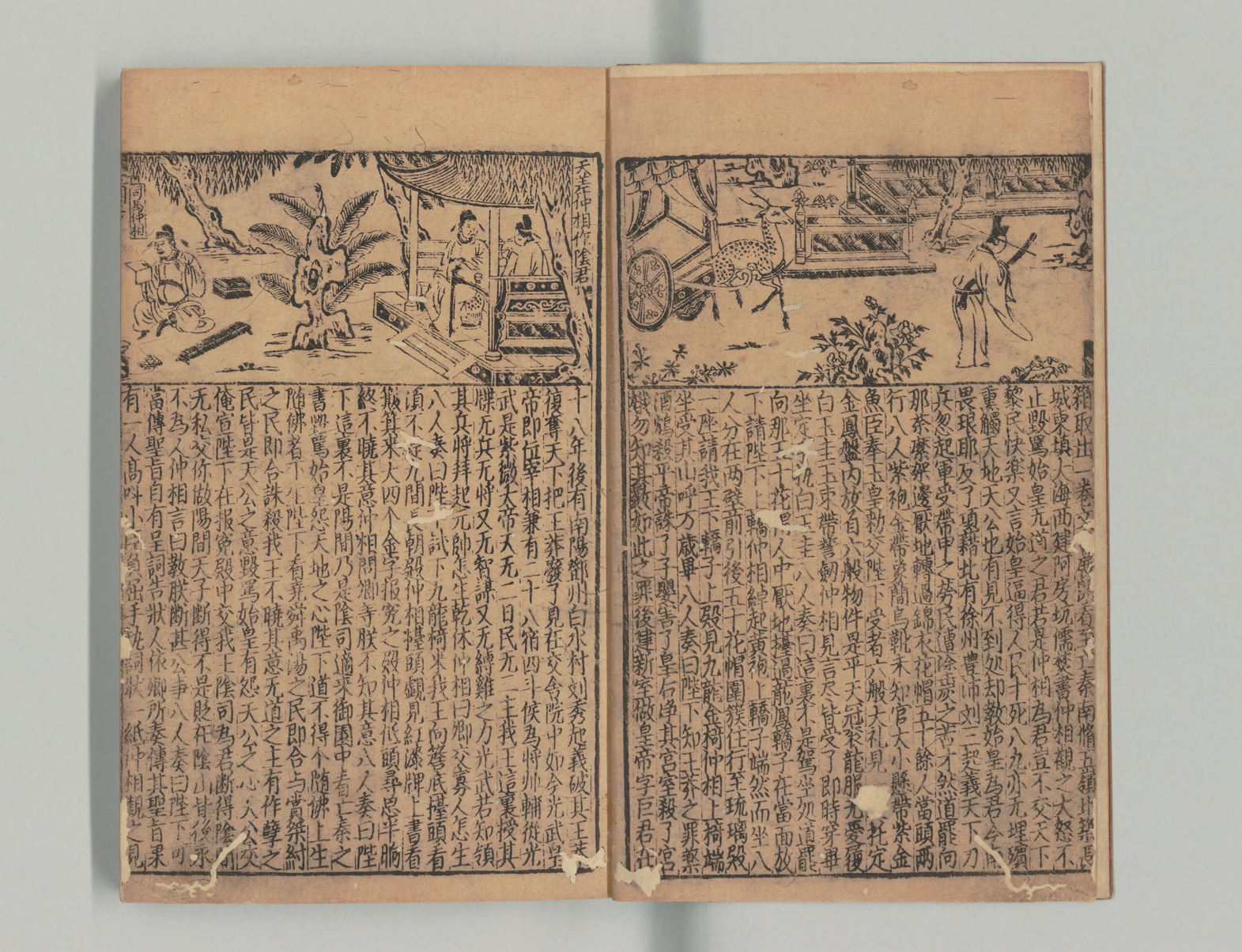

The National Archives of Japan also holds Zenso Heiwa, published by Jian’an-yu of Fujian, China during the Yuan Dynasty.

Stories compiled in the period of Yuan Dynasty

Historic tales published in the Zhizhi period under the Yuan Dynasty

Historic tales published in the Zhizhi period under the Yuan Dynasty

Series of popular Chinese historical stories, including Sangokushi (The Romance of the Three Kingdoms), published in Jian’an County, Fujian Prefecture, Jiangzhe Province, in the Zhizhi period (1321-23), are stored in Japan. Zenso means that illustrations related to the stories are printed on each page, while "Heiwa" means "storytelling text." No copies are preserved in Mongolia and China, and it is the only existing copy of this material in the world.

This document was widely popular during the Yuan dynasty. It is not certain when this document was introduced to Japan, but this material shows that documents from the Yuan dynasty were introduced to Japan.

This material was held in the Momijiyama Library before being succeeded by the government of Meiji, and now in NAJ’s Cabinet Library collection. In 1955, this material was designated as Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government.

Mongol Invasions had a strong impact on Japan. After that, battles of various sizes and military tensions continued.

Time passed, it was not until the 19th century that new opportunities for exchange arose and records appeared.